Shielding effect of the atmosphere on a distant cloud

In the event of a major accident or atomic bomb tests, clouds containing radioactive dust can pass over populated areas.

These radioactive clouds, the most famous being that of Chernobyl, have become a legitimate source of fear and part of the collective imagination.

The dust emits radiation that can reach the ground, causing an external exposure lasting for the duration of the cloud’s passage.

However, if the cloud passes at high altitude, this exposure is greatly reduced by the shielding effect of the atmosphere.

When radioactive materials are released, only gamma rays are capable of irradiating at a distance.

So, how much protection does the atmosphere provide against these rays?

The first protection comes from a purely geometric effect: the angle—called the solid angle—under which a target is seen decreases rapidly with distance. But the medium traversed is not a vacuum. The atoms in the air absorb gamma rays.

This shielding effect, negligible over a few meters, becomes significant beyond a few hundred meters.

Without this atmospheric shield, life could never have developed on Earth, constantly bombarded by cosmic radiation.

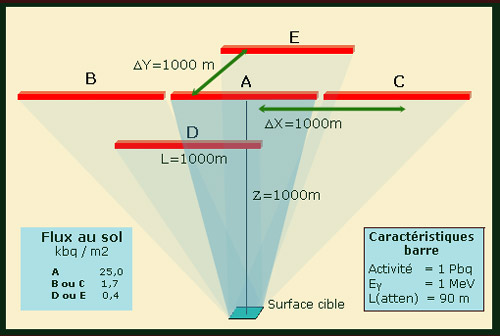

Example of a geometric effect: radioactive fluxes at 1000 m altitude

The risk resulting from the passage of a radioactive cloud is measured by the flux (number of gamma rays per second) crossing a target surface on the ground.

The figure shows the ground flux resulting from several radioactive bars 1 km long located at an altitude of 1000 m.

The ground flux from bar A, directly above the target, is 14 to 60 times greater than that from bars B, C and D, E offset horizontally by 1 km.

Exposure is mainly due to radioactivity located vertically above the point.

If the cloud moves, a peak in exposure will be observed when it passes directly overhead.

© IN2P3

Let us consider the idealized case of an intense source of 1 MeV gamma rays moving at an altitude of 1000 m.

Gamma rays of 1 MeV are not the most representative in an accident scenario, but they are among the most penetrating:

they must travel 90 meters of air for their number to be reduced by half.

Now suppose that the source has a reference activity of 1 PBq (one thousand billion kilobecquerels or 27,000 curies),

and that this activity is uniformly distributed along a 1 km bar for simplicity of calculation.

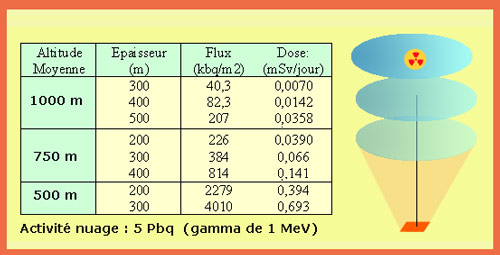

Influence of altitude and cloud thickness

Calculation showing how altitude and thickness of a radioactive cloud influence the ground-level gamma flux and received dose.

A cloud activity of 5 PBq and penetrating 1 MeV gamma rays were chosen.

The ground flux (number of gamma rays per second crossing a 1 m² target) was evaluated directly beneath the cloud,

and the daily dose was calculated assuming that all gamma rays crossing the target were absorbed by an 80 kg human body.

The cloud radius—assumed circular—is 1 km with a Gaussian activity distribution.

Flux and dose increase with thickness, and for lower layers closer to the ground.

© IN2P3

If the risk is evaluated by the flux of gamma rays passing through a 1 m² target on the ground,

the calculation shows that this flux is maximum when the bar is directly above the target: 25,000 gamma per square meter.

In a vacuum, this flux would be 2800 times more intense, due to the absorption of air.

The flux decreases very quickly as soon as the bar moves away from the vertical.

If it moves, a peak in exposure will be observed when it passes directly overhead.

What dose would a human subject receive if they stayed under the cloud for a whole day,

and their 80 kg body absorbed all 25,000 gamma rays of 1 MeV per second?

The calculation shows that the daily exposure would reach 0.004 mSv,

a risk equivalent, according to some experts, to smoking a quarter of a cigarette.

Impressive as the becquerel numbers may sound, they can be misleading!

The shielding effect of air increases with altitude.

Conversely, it decreases when the intense radioactive source approaches the ground target.

In our example, the flux can reach millions of becquerels at a vertical distance of 500 m.

It becomes imperative to seek shelter—a ceiling or wall of 30 cm of concrete has the same absorbing power as 1 km of air.

This was experienced by the helicopter pilots during the Fukushima accident,

when they attempted to drop seawater on buildings emitting deadly gamma radiation they could not approach safely.

These simplified calculations give an idea of the protection provided by the atmosphere, through a few orders of magnitude.

It should be remembered that air layers providing good protection against very intense gamma sources are on the order of a kilometer thick,

and that below this level, protection rapidly diminishes.

An exact calculation would need to take into account that gamma rays are not absorbed all at once.

When they disappear through the Compton effect, they transfer part of their energy to a secondary gamma ray emitted in another direction.

At great distances, the gamma rays that reach the target have lost much of their energy.

Having traveled a longer path than the direct line, they have a greater chance of being absorbed along the way.

Moreover, the emitting nuclei in the cloud do not belong to a single isotope.

The full energy spectrum of the gamma rays must be considered.

Focusing only on iodine-131 and cesium-137—the main components of the Chernobyl cloud—

the principal gamma energies are 364 keV for iodine and 662 keV for cesium.

They are absorbed more quickly than the 1 MeV gamma rays in the example.