The core of the atom

Almost all matter in the Universe is concentrated within atomic nuclei. Some 100,000 times smaller than the atom, they contain 4,000 times more mass than their orbiting electrons. All nuclei are made up of neutrons and protons, collectively known as nucleons, which play similar roles in maintaining the structure of the nucleus. Whereas electrons can be said to be ‘fundamental’ (or indivisible) particles in their own right, nucleons are made up of quarks, the smallest known units of matter, and as a result are not considered to be fundamental particles.

The existence of quarks has imposed itself since the 1970s. In the field of nuclear physics which is that of radioactivity, the habit before was to consider the nucleons as the elementary constituents of the nucleus. For simplicity, we will keep this convention, referring to the internal structure of nucleons and quarks only when necessary.

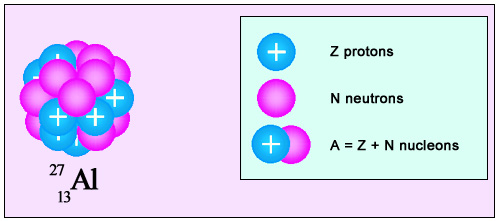

Composition of an atomic nucleus

The nucleus of aluminium comprises 27 nucleons: 13 protons and 14 neutrons. As protons have a positive electric charge, equal and opposite to that held by electrons, 13 electrons are needed to overcome the nucleus charge, and form one atom of aluminium. As protons and neutrons have approximately the same mass, each weighing almost 2,000 times as much as an electron, the mass of the orbiting electron body is negligible when compared to that of the nucleus.

© IN2P3

The classical representation of the nucleus is a dense grouping of protons and neutrons, defined by three mathematical numbers: Z, N and A. Z represents the number of protons, N the number of neutrons, and A the total number of nucleons. As both protons and neutrons are referred to as nucleons, A is simply the sum of N and Z: A=N+Z. The two fundamental properties of a nucleus are its mass and its electric charge. As protons and neutrons have approximately the same mass, A is a convenient measure of the mass of the nucleus.

The electrical charge of the proton (taken as a conventionnal unit), however, is different from that of the neutron: a proton has a charge of +1, and a neutron, being neutral, has a charge of 0. As a result, Z is used to calculate a nucleus’s charge.

For all nuclei naturally present in the Universe, Z varies from 1 to 92, and A from 1 to 238. The heaviest natural element is Uranium-238, which contains 92 protons for 146 neutrons. The nucleus, therefore, has a combined mass of 238 nucleons, and a charge of +92.

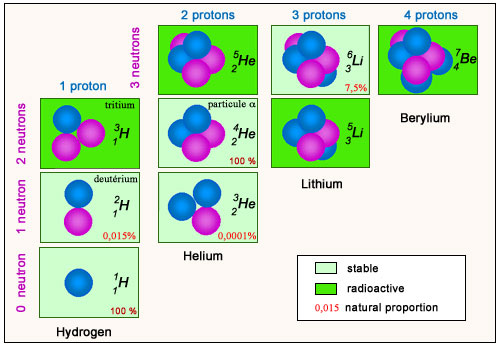

Light nuclei

The beginning of the map shows how protons and neutrons agglomerate in order to form light nuclei, hydrogen, helium, lithium and berylium isotopes. All the nucleons have been drawn visible. The number of protons has been limited to 4, that of neutrons to 3. Radioactive isotopes are unstable and are thus absent from our environment. The proton (ordinary hydrogen) and helium-4 (alpha particle), which are stable, together form more than 99% of the mass of the universe.

© IN2P3

If protons are positively charged and neutrons are neutral, then the electron is the conveyor of negative charge. It has a charge of -1, exactly equal and opposite to that on the proton. In any complete atom, the number of protons in the nucleus is precisely equal to the number of electrons orbiting it; meaning that the atom’s total charge is equal to zero.

It may seem unusual, at first glance, that the nucleus has any sort of stability whatsoever. Being comprised entirely of positive and neutral particles, and remembering the law of electromagnetism that ‘like charges repel’, it would be expected that any nucleus would fly apart very quickly. The paradox is irresolvable in terms of classical physics, and was only explained away in the middle of the 20th Century, with the discovery of a very strong force which exists over very short distances inside the nucleus. This ‘strong’ force acts like a nuclear glue, overcoming the electrostatic repulsion between the protons and maintaining the nucleus’s stability.

Articles on the subject « The atomic nucleus »

The proton

The charged constituent of the nucleus The nucleus of the hydrogen atom consists of one solitary [...]

The Neutron

The neutral partner of the proton The neutron is, along with the proton, one of the two constitue[...]

Isotopes

Nuclear variants of a given atom … Free of all electric charge and present only in the nucleus, n[...]

Nucleus Energy Levels

Analogies with the atomic energy levels … At first glance, nuclei seem to be very different[...]

Quarks and leptons

The fundamental constituents of matter On the most elementary scale, the world around us is made [...]

Quarks and Gluons

How quarks interact within nuclei … To describe radioactivity and nuclear reactions such as[...]

Matter and Antimatter

Nature loves symmetry. However, one can not dream of a matter less symmetrical than the matter wh[...]