A thin line between nuclear energy and atomic weapons

How can we guarantee access to peaceful nuclear energy while simultaneously preventing the development of atomic bombs? Are non-proliferation treaties and IAEA inspections enough to ensure international security? The question of proliferation, as old as the ‘Atoms for Peace’ initiative itself, has lost none of its relevance; as can be seen from the cases of Iran and North Korea.

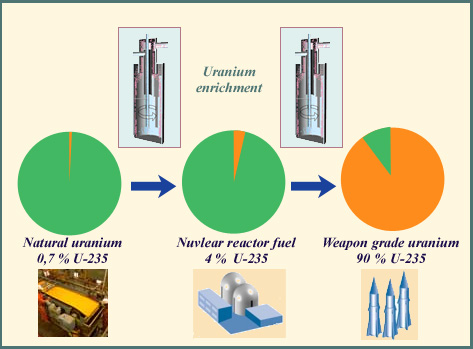

Civilian and military uranium

The natural uranium that is extracted from mines is very poor in the fissile nuclei of uranium 235. It has to be enriched 5- or 6- fold (going from a 0.7% uranium 235 content to 3-4% of uranium 235) in order to be an effective fuel for commercial reactors; an enrichment which can be achieved by gaseous diffusion or centrifuging techniques. If the percentage content is upped to around 90%, then the resulting uranium is rich enough to be used in the manufacture of atomic bombs. Mastering these enriching techniques is a vital step in the acquiring of nuclear capability.

© IN2P3

The most important ingredient for an atomic bomb is weapons-grade quality uranium or plutonium, which is to say fuel that consists almost entirely of the fissile isotopes uranium 235 and plutonium 239. Obtaining even 10 or 20 kilograms of these radioisotopes – the critical mass required for a nuclear weapon – fortunately still requires extremely complicated procedures. There are currently two possible methods: the uranium pathway, which involves the isolation of the 0.7% of uranium 235 nuclei present in natural uranium, and the plutonium pathway, which relies on the production of plutonium 239 in specially-built reactors.

At the core of the proliferation issue is the question of access to these fissile materials and the technology required for their production. A thriving black market in nuclear fuel (luckily still dealing with small amounts) sprung up in the years of anarchy which followed the fall of the old Soviet Union. In 2004, the scientist responsible for the Pakistani nuclear bomb was revealed to be behind a worrying trade of centrifuges used in the enriching of uranium.

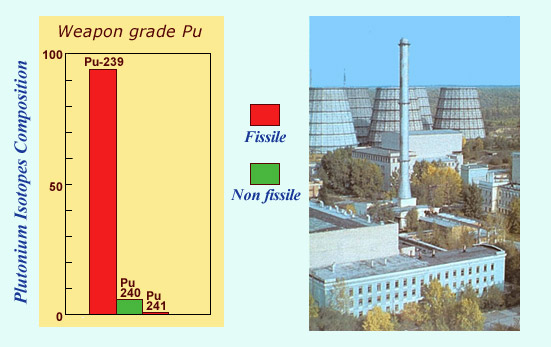

Weapons-grade plutonium

The plutonium used in atomic bombs is richer in the 239 isotope than any produced by civilian reactors, containing in excess of 93%. This type of plutonium, specifically designed for the production of atomic bombs, is generally produced in special reactors, such as this Russian one from the Tomsk-7 site in Siberia.

© IN2P3 andCEA

When a country is seeking to acquire a nuclear arsenal, the argument that such a stockpile serves as a deterrent is bound to be put forward sooner or later. Though this type of policy has not yet led to nuclear war, a far safer strategy would be to create an international climate where a nuclear deterrent would be irrelevant. Most countries have renounced all plans to obtain one, including such advanced nations as South Africa or Brazil.

The terrorist attacks of the 11th of September 2001 irrevocably changed the global situation. The United States began advocating preventive military strikes, a policy that requires meticulous intelligence gathering and preparation. The absence of the weapons of mass destruction used to justify the Iraq war has spread doubts in many minds as to America’s good faith on this critical issue.

Pakistani networks

The use of centrifuges allowed Pakistan to follow India into the nuclear club. Abdul Qadeer Khan, the father of the Pakistani bomb, worked in the Netherlands from 1972 to 1975 as an engineer in a nuclear enrichment plant before taking the technology home with him in his luggage. Treated as a national hero and loaded with honours, the general started a centrifuge trade with Iran and Libya as his main clients. Finally accused in 2004, Abdul Qadeer Khan obtained the forgiveness of then President Musharraf after a public confession

© DR

In North Korea, a desperate regime sought salvation through plutonium enrichment and was able to carry out a nuclear test at the end of 2006. Iran has also develop enrichment technology in order to provide fuel to future nuclear power plants while denying any desire to create an atomic bomb.

Iran’s efforts to acquire nuclear power technology collided with an American scenario where all complex and exportable technologies (such as fuel enrichment and reprocessing) would be limited to a selected and select group of nations. These carefully vetted countries will take it upon themselves to supply others with fuel, and will be responsible for recycling all their radioactive waste.

Will we be forced to adopt such an inequitable distribution of energy to combat the risks of nuclear proliferation? To avoid this possible outcome, it is vital to end all those national and international conflicts which are causing instability and encouraging reversion to nuclear deterrents. The United States may favour a firmer approach, based on economic sanctions and possible military interventions, but an organised, peaceful and equitable world is the best guarantee against proliferation risks.

Articles on the subject « Nuclear Proliferation »

The uranium pathway

Centrifuging and enriching uranium 235 Taking the uranium pathway towards proliferation, the key [...]

The plutonium pathway

Extracting weapon-grade plutonium from spent fuel For the plutonium pathway, the key technology i[...]

Iranian Centrifuges

Technical Challenges: IR-1 and IR-2 Centrifuges Uranium enrichment requires significant technical[...]

North Korea

A country cut off from the world that blows hot and cold… The Democratic People’s Rep[...]