Monitoring exposure to neutrons

Neutron dosimetry is only necessary in the presence of a neutron flux, generally near nuclear reactors or certain particle accelerators.

Neutron dosimetry is more complex than photon or beta-electron dosimetry:

while the latter produce direct (electrons) or indirect (photons) ionization,

neutrons are detected mainly through their interactions with specific atomic nuclei.

These interactions generate charged particles, which the neutron dosimeter detects if such interactions (called conversions) occur within the device.

It is important to distinguish between slow or thermal neutrons (very low energy) and fast neutrons, as their behaviors differ significantly.

Examples of neutron dosimeters

Neutrak dosimeters, marketed by Lcie-Landauer, are an example of passive dosimeters for neutron radiation detection.

Depending on the model, they are suitable for detecting slow (thermal), intermediate, and fast neutrons.

© Lcie-Landauer

Neutron dosimetry uses various characteristic signatures (or conversion modes) to identify and measure the presence of neutrons.

– In a highly hydrogenated medium, collisions with hydrogen protons quickly slow down fast neutrons.

The resulting recoil protons ionize and can thus be detected.

They can also be observed through their tracks in a photographic emulsion.

– A typical interaction of slow neutrons is their capture by a lithium-6 nucleus, which represents 7.5% of natural lithium.

The capture splits the lithium-6, ejecting an alpha particle — a signature that can be detected by a dosimeter.

A similar capture reaction occurs with boron-10.

– In film dosimeters, a cadmium screen placed over part of the film helps estimate the dose contribution from thermal neutrons, as cadmium absorbs slow neutrons.

– Some photographic dosimeters use an emulsion in which, after development, the tracks of recoil protons resulting from neutron interactions are visible.

This technique only detects fast neutrons, which limits its use to monitoring installations equipped with accelerators.

– Thermoluminescence can also be used, taking advantage of the fact that certain thermoluminescent materials are sensitive to

X-rays, gamma rays, and neutrons (for example, lithium-6 fluoride).

This method is better suited for detecting slow neutrons.

– Photographic emulsions can also be read after development.

Neutrons leave so-called latent tracks in these emulsions, produced by the ionization of particles resulting from neutron interactions

in hydrogen-rich media (for fast neutrons) or materials enriched with boron and lithium (for slow neutrons).

These dosimeters take time to process but are now compatible with automated reading as long as the track density remains moderate

(typically up to 200 mSv). Their sensitivity is fairly good.

– Bubble dosimeters exploit the property of nuclei set in motion by neutron interactions to become highly ionizing.

In a metastable gel, ionization causes the vaporization of microdroplets, forming bubbles that remain trapped in the gel.

Counting the bubbles provides an estimate of the received dose.

An optical or electronic system can monitor bubble formation and trigger an alarm.

The dosimeter can be read at any time and reset by recompressing the bubbles.

This type of dosimeter is very sensitive (down to a few microsieverts) but must be fairly large (a so-called “handheld dosimeter”).

It is sensitive to shocks and its lifespan is limited by the number of possible resets (around 3 months in practice).

– Electronic dosimeters suitable for neutrons are currently under development.

They use diode or mixed dosimeters equipped with hydrogenated, boron, or lithium converters.

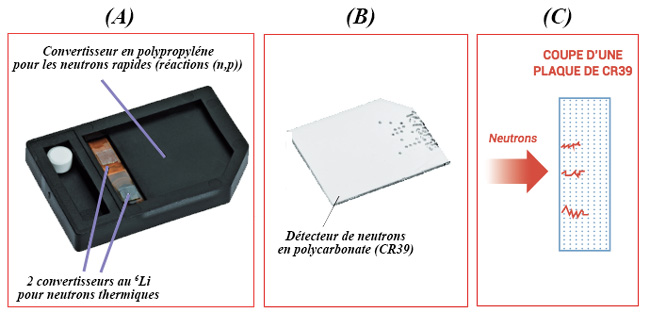

IRSN neutron dosimeter

The dosimeter shell converts neutrons into charged particles (A):

for fast neutrons, by collisions with hydrogen protons in the polypropylene casing;

for slow neutrons, by nuclear reaction with lithium-6.

Then (B), the charged particles from converted neutrons leave a track in a polycarbonate detector, which records them.

Finally (C), when this detector is later immersed in an alkaline sodium hydroxide solution, the tracks are revealed and can be counted under a microscope.

The number of tracks allows the dose to be determined.

© IRSN

The IRSN also provides a neutron dosimeter.

This dosimeter is suitable for all neutron spectra—thermal, intermediate, and fast—encountered in industry, research, and the medical sector.

It is called the “RPL neutron” dosimeter, as it also includes an RPL glass detector capable of measuring, in addition to neutrons,

beta, gamma, and X radiation through radiophotoluminescence.

The neutron dosimeter consists of a polycarbonate detector (CR-39) enclosed in a polypropylene shell used as a converter for detecting fast neutrons.

For slow neutrons, cadmium is used—a metal very effective at absorbing them.

Two additional lithium-6 fluoride converters are used to verify that the dosimeter has indeed been irradiated and to determine the “thermal neutron” dose equivalent.

IRSN: Neutron dosimetry data sheet

See also:

Thermal neutrons

Fast neutrons