Knowledge of our heritage : Analysis of historical artefacts

Scabbard of the emperors’ sword

The scabbard of the emperors’ sword was given to Napoleon Bonaparte in 1797, and has since been preserved at the Fontainebleau museum near Paris. After the end of its Italian campaign, the defeated Austrians were forced to sign the treaty of Campo-Formio. As a symbol of their defeat, the commanding Austrian generals offered Napoleon a sword that had belonged to the Emperors of the Holy Roman Empire. The French Directoire complemented the gift by awarding Napoleon a magnificent golden scabbard. Modern analysis has shown that the scabbard is made of solid gold and that the Directoire spared no expense when it came to rewarding the brilliant general.

© LRMF

At first glance, it seems that radioactivity and nuclear physics are poorly relevant to archaeology or art history. Nuclear techniques, however, provide fast, safe and sensitive ways to determine the nature, the provenance, the technique of manufacture and even the age of historical objects; making them indispensable tools in the examination of our past.

Testing the thickness of gold

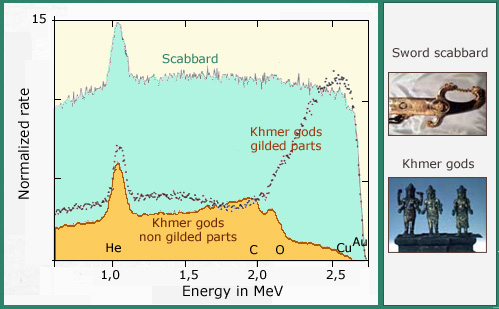

The technique used to compare the gold in the emperors’ scabbard with that from the Khmer statue in the Guimet museum is known as ‘Rutherford backscattering’ (or RBS). The results can distinguish very clearly between the solid gold of the scabbard and the gilding used on the statuette.

© LRMF

The internal structure of a piece of marble, for instance, is distinctive of the quarry from which it was mined. Analyses of the chemical components present in such a sample of marble allow for accurate identification of the source quarry without any damage to the sample itself.

Is the ruby set on an ancient ring a fake or a genuine precious stone? Fortunately, a sample of the ruby is not required to find out the answer. By measuring the quantity of natural impurities present in a gemstone, one can accurately determine its authenticity.

Three Khmer gods

The surface of this Khmer statuette, stored in the Guimet museum in Paris, has areas that are both gilded and plain. Nuclear testing allows for an in-depth analysis of the quality of the gold of the statuettes.

© Dominique BAGAULT/LRMF

The inks used on ancient documents, whether on papyri or in the production of illuminated manuscripts, all have noticeably different compositions. Analyses of these inks allow modern historians to detect otherwise imperceptible inconsistencies; such as when a copy of Cicero’s Philippicae contains passages added on by a Medieval scribe.

The most valuable technique that radioactivity has offered this field is that of radioactive dating. From objects only a few hundred years old (such as the shroud of Turin) to those going back some tens of thousands of years (ashes found in the Chauvet cave), the decay rate of carbon-14 is able to provide an accurate age.Though the use of radioisotopes is perhaps the most widely-known dating technique, it is by no means the only one available to historians. Thermoluminescence (a measure of the light an object gives off when it is heated), for example, is frequently used by anthropologists to date the remains of prehistoric humans alive at the time of Homo Sapiens. In museums, thermoluminescence is used to differentiate between genuine pre-Columbian clay statuettes and the widespread modern counterfeits.

The dating methods outlined above are, unfortunately, not always capable of the expected degree of accuracy. They are, however, almost entirely impossible to fool.

Articles on the subject « Object Analysis »

Components Analysis

Analysis of surface chemical elements to identify materials The identification of raw materials e[...]

Find materials origins

The impurities witness the origin of precious stones Knowing the background of the material gives[...]

Techniques of fabrication

The know how of artisans in the past Many important clues about the fabrication technique of heri[...]