Activities Born of Long Isolation?

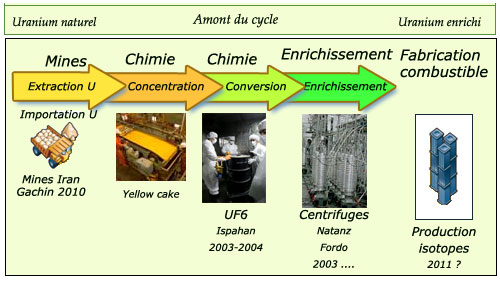

Thirty years of embargo and isolation forced Iran to rely on itself. In the field of civil nuclear energy, it sought autonomy by developing the upstream stages of the fuel cycle—from uranium mining to fuel fabrication for a reactor: uranium ore extraction, purification and conversion, enrichment, and finally the production of fuel elements.

These steps, while legitimate in the case of civil nuclear energy, were met with suspicion—especially the critical stages of conversion and enrichment of uranium-235, which were even seen as provocations.

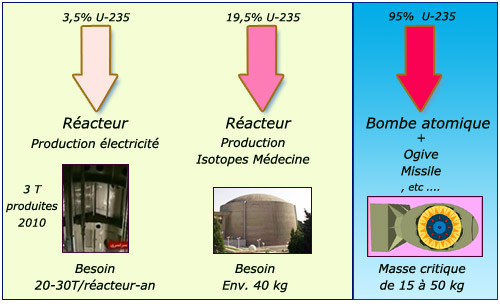

In 2009–2010, as Iran had not yet mastered the production of fuel elements, a proposed exchange was discussed: one ton of low-enriched uranium produced at Natanz in return for 20%-enriched fuel elements for a Tehran reactor intended for medical use. This initial gesture of cooperation, which could have broken the vicious cycle of mutual mistrust, ultimately failed. The failure led Tehran to enrich a few dozen kilograms to 20% and to attempt to manufacture its own fuel. In December 2011, Iran announced it had mastered the final stage of fuel fabrication for its research reactor. Following the interim agreement signed in Geneva at the end of 2013, Iran destroyed, through dilution according to the IAEA, its surplus stock of 20%-enriched uranium.

The Quest for Autonomy

The desire to avoid dependency on hostile partners led Iran to seek autonomy in its nuclear activities and to develop itself the upstream stages of the cycle from uranium ore to fuel fabrication. On December 5, 2010, Iran succeeded in producing its first yellowcake (uranium concentrate used as a base for enriched uranium production) from ore extracted at the Gachin mine, whereas it previously had to import uranium ore. The final stage of producing fuel elements for the Tehran reactor was said to be imminent.

© IN2P3

Nevertheless, the quantities involved were small. By the end of 2010, the centrifuges at Natanz had enriched just over 3 tons of uranium to 3.5%—not nearly enough to fuel the new Bushehr reactor, whose fuel is Russian. For comparison, France enriches nearly 2,000 tons annually to supply its 58 reactors.

On June 9, 2010, the Security Council adopted a new round of sanctions. These were further intensified outside the UN by the United States, followed by the European Union. The aim was to force the regime to the negotiating table by targeting the country’s economy (oil, banks) through sanctions that also affected the general population. President Obama’s December 2011 decision to directly target oil exports—the main source of national wealth—resulted primarily in hardship. Europe followed suit, and the oil embargo took effect in July 2012. What can be said about a policy designed to stifle the economy and which primarily affects an innocent population? Will the regime bend under pressure? Or will it be strengthened? Historically, blockades tend to unify nations!

The crisis illustrates how the risk of proliferation is increasing due to technological advances. The only effective long-term solution is to convince countries that acquire the necessary know-how that they are not threatened, and that pursuing nuclear deterrence is both unnecessary and costly. Unfortunately, the escalation of sanctions, which deepens the chasm of mistrust and mutual paranoia, moves in the opposite direction.

What to Do with Enriched Uranium?

By the end of 2010, the centrifuges at Natanz had enriched just over 3 tons to 3.5%, far short of the 20 to 30 tons per year required to fuel a reactor like Bushehr: 8,000 centrifuges were installed, some inactive, while 50,000 would be needed! However, the quantity was sufficient, when enriched to 20%, for the small reactor producing medical isotopes!

© IN2P3

Is Iran’s nuclear program civilian? The existence of the program came to light in 2002, when an Iranian dissident revealed an underground facility at Natanz intended for uranium enrichment. Iran was resuming activities suspended since the Shah’s era, during which uranium enrichment was meant to accompany an ambitious reactor program. Following these revelations, Iran submitted to IAEA inspections in accordance with the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and considered ratifying the additional protocol to the treaty in 2003–2004, which allows for more robust and unannounced inspections.

Since 2002, Iran has been accused of hiding a military program. Yet all Iranian leaders have claimed that the nuclear activities are purely civilian, including President Ahmadinejad, known for his provocative rhetoric. It is noteworthy that since the 2002 revelations, there have been no major leaks or defections indicating a military dimension, despite the strong opposition to the regime, particularly evident in 2009.

Finally, it should be noted that uranium enrichment requires advanced technology that is difficult to master. Had Iran truly sought a bomb, it would have been much faster to follow North Korea’s example, which produced weapons-grade plutonium with a small reactor… entirely outside international oversight.

This does not mean there is no temptation toward nuclear deterrence, especially in the face of threats. France itself followed this path during the time of General de Gaulle and the Cold War.

BACK TO PAGE Iran Nuclear Crisis